Lean Apps Part 2: The Elements of a Lean App

Defining the ideal model of what a software application should look like

In Part 1 of this series we gazed into the rearview mirror to see how software has evolved towards lower “surface area” over time. But what does all this tell us about the future of software development? If the major trends have been focused on the continual removal of surface area (and the resulting decrease in complexity and cost of ownership), what’s the eventual result?

If we imagine these trends continuing, it’s also natural to ask an interesting question:

- What else can we take out?

- What undifferentiated heavy lifting can be eliminated, leaving only the truest, most pure form of what is often referred to as “business logic”?

- In other words, what does a fully lean app look like?

What can you stop doing?

For an industry that has for so long defined “software” as “stuff that runs on a machine”, it can be hard to wrap your head around the idea of giving up on that paradigm. One way to approach it is to focus on customer value: What are the parts of an application that actually create end user value?

For instance, when you patch an OS, your end users don’t care. At best, it protects them from some future security or operational event, but it’s not something they can directly perceive…and they don’t care if your company does it or if your infrastructure provider does it for you. In other words, an activity like that is utterly undifferentiated – a developer patching the OS on a server isn’t likely to help their company outcompete the competition or enter a new market (unless that company happens to be a cloud provider, operating system producer, or server vendor themselves).

So what’s the actual beating heart of a typical application, the part that we couldn’t actually forgo? We often hear the term “business logic” tossed around, but what does that actually mean?

The elements of a lean app

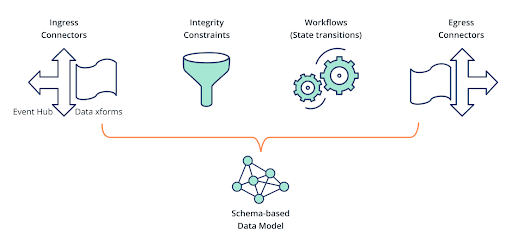

If we allow ourselves to let go of how an application is constructed today and instead think about it structurally, there are several elements that embody the actual business needs of a typical application (Figure 2):

A data model

Most commercial applications are, at their heart, “CRUD” in nature – whether it’s buying toilet paper on Amazon, filling out an insurance claim form, or paying a bill online, much of software is ultimately about reflecting real-world changes (a buyer’s desire to purchase something, a form being filled out) with a durable replica (aka “database update”) of those facts, and that requires knowing what kind of data a business needs to model in the first place.

Integrity constraints

Once you have the “syntax” of a data model in mind, the next question is usually establishing the “semantics”, most notably what kind of data is good versus bad data.

For example, most US banks won’t allow you to withdraw more money than you have in your checking account, so in a banking application, attempting a withdrawal would usually start with the software equivalent of asking, “Is the current balance greater than or equal to the withdrawal amount?” If not, the withdrawal isn’t valid. Note that we haven’t said how integrity constraints are expressed – they could be data- or logic-centric expressions (“balance >= $0.00”) or require Turing-complete code to calculate, possibly relying on existing data in the data model to determine the answer.

Like the data model itself, integrity constraints are pure business logic – advances in telepathic AI aside, there’s no way for a vendor or piece of infrastructure to know what it means for data to be “right” for any given business (though choices in how the data model is expressed – the schema – might make the expression of integrity constraints easier or more difficult).

State transitions (aka data triggers)

What do Oracle PL/SQL routines, AWS Lambda functions triggered by an Amazon S3 file upload, cron jobs, and Microsoft Azure LogicApps have in common? They’re all workflows, ways of managing transitions from one application state to another, whether that transition is time based (“run a cron job at midnight”, “retrieve the tweets on a specific subject from the last hour”) or data centric (“when the balance of a checking accounts exceeds $1M, transfer the excess to a savings account”).

State transitions might employ integrity constraints, particularly if they create new or modify existing data items, but they are fundamentally machine initiated and managed, rather than representing end user input or output. Business workflow modeling is one of the key reasons that software (and thus applications) need to be stateful and Turing complete, because they can’t be reduced to stateless or trivial pattern representations in most cases.

Connectors

Connectors are the ligaments that enable an app to connect to other applications. Connectors have two conceptual elements, though they may be combined in practice:

- Data transformations. These modulate differences between the app’s data model and one or more “foreign” data models.

- Event hubs. Other applications that lack proper eventing, scaling, or buffering mechanisms may require not only data transformation but also control integration, ranging from polling (for ingress) to queuing and throttling updates (for egress).

It’s tempting to think of connectors as “impure” – and to be certain, often their role will be to make up for shortcomings in legacy applications or systems that exist outside the lean app regime we’re defining here. But even in a perfect world of only lean apps communicating with other lean apps, the need to build and deploy independently (“microservices” versus “monoliths”) means that they will need to be loosely coupled, rather than tightly bound to everything.

That means connectors have an important long-term role to play in modulating inter-application schema and workflow evolution, as well as their short-to-medium term role in assisting with the initial migration from a legacy app to a lean app and its integration with other legacy systems not yet ready for modernization.

Figure 1: The elements of a lean app

The list above (see Figure 1) is pretty short :), and at first blush might seem too short: If you compare it to a “typical” application, such as a Kubernetes-based app, it’s perhaps 1-3% of the total amount of software (and deployment/operational) infrastructure normally thought of as an application. And just looking at the list above, even with an eye toward public cloud infrastructure, you’d be forgiven for reacting with, “But wait…there’s so much more”.

And that’s certainly true today: There is a critical gap between the list above – true business logic – and the application services developers are using today.

To make a lean app possible, the infrastructure has to start doing more for application developers. In the next installment we’ll look at the elements of a typical application that shift from the developer to the infrastructure.

Next post – Lean Apps Part 3: Letting Infrastructure do the Dirty Work

In the Part 3(coming soon) of this series, we cover what infrastructure needs to do automatically and without impacting developers or operators.

Get the whitepaper

If you don’t want to flip through four separate posts, you can download the full white paper here.

Build a lean app

It’s possible to create lean apps today. Companies like Vendia will let you move directly to a lean app methodology for new application development or to layer a significant new feature or capability on top of an existing application. You can get started for free and deploy a sample lean app in less than ten minutes here.

Where wholesale adoption of the idea isn’t (yet) possible, developers and companies still benefit from the concept through incremental steps in various areas of application development. Contact us and we’ll help you learn how to start applying a lean approach to your development today.

About the author

Dr. Tim Wagner, the “Father of Serverless,” is the inventor and leader responsible for bringing AWS Lambda to market. He has also been an operational leader for the largest US-regulated fleet of distributed ledgers while VP at Coinbase, where he oversaw billions in real-time transactions. Dr. Wagner co-founded Vendia with Shruthi Rao in 2020 and serves as its CEO and Chief Product Visionary. Vendia’s mission – to help organizations of all sizes easily share data and build applications that span companies, clouds, and geographies – is his passion, and he speaks and publishes frequently on topics ranging from serverless to distributed ledgers.

t: @timallenwagner